Oil & Gas Benchmarking

Setting The Standards in Ultra High Value Oil & Gas Benchmarking for 24 Years

- Specialist "transformation" benchmarking data partner to senior executives at leading energy companies.

- Wonder why board-level executives trust Fulcrium as their exclusive benchmarking partner for high value-identification?

- $8bn new value identified for one oil & gas client on one transformation benchmarking data engagement alone. Verified. Achieved. That is the Fulcrium data difference.

- Benchmarking service focused solely on extraordinary-value opportunity identification to drive transformation and breakthrough performance improvement.

Andrew Gould - Chairman & Chief Executive, Schlumberger

Benchmarking to drive exceptional competitive performance in upstream oil & gas.

Paul Beijer, VP – Strategy, Planning & Assurance, Shell

Benchmarking in oil & gas for driving performance to make Shell an industry leader.

Julio Dal Poz - Senior Strategy Advisor, Equinor - Statoil

Benchmarking in upstream oil & gas to drive efficiencies and performance improvement.

Sir Jim Ratcliffe - Chairman, INEOS Chemicals

Benchmarking-driven operational performance excellence in petrochemicals.

Dere Ogbe - Head of Competitive Intelligence, Shell

Benchmarking in a “purpose-driven” way to compare performance in the oil & gas industry.

Ann-Christin Andersen - Director, TechnipFMC

Benchmarking to drive performance and generate savings in the upstream supply chain.

Dr Dominic Emery

Chief of Staff, BP

Benchmarking-driven performance improvements in upstream mega-projects.

Giorgio Delpiano, Senior Vice President, Retail & Commercial, Shell

Benchmarking-driven performance improvements in the integrated fuels value chain from crude to customer.

We only assist the most forward thinking, progressive and ambitious Oil & Gas companies in the world

- Their cultures are designed to build shareholder value consistently and to thrive through good times and bad.

- When circumstances change, and they need to respond fast, they call on us for expert high value performance benchmarking.

- We deliver high-value opportunity identification, increased efficiencies, and breakthrough performance improvements – within short timescales.

- Drawing on Fulcrium's proprietary global oil & gas benchmarking database and metrics established for over 24 years.

- Our service is complemented by a range of global primary and secondary research capabilities – utilising multiple, independent sources – enabling rapid additions to benchmarking data in real time.

- Fulcrium only focuses on oil & gas benchmarking for transformative-value opportunity identification.

ExxonMobil outperformed peers in 2024

- ExxonMobil is outperforming its peers and national oil companies through industry-leading share price performance and remarkable shareholder returns.

- Fulcrium Benchmarking reveals why ExxonMobil is the leader and what it takes to drive best-in-class oil and gas performance.

Domain Specificity in Oil & Gas

We use our proprietary frameworks to undertake a wide range of core Value Chain and Functional Benchmarking.

Exploration

Development & Extraction

Manufacturing & Energy Production

Transport & Trading

Sales & Marketing

Segments

- Oil and Gas

- Exploration, Development, Production

- Decommissioning

- Refining, Marketing, Trading, Transport

Disciplines

- Capital Projects, Engineering & Technology

- Drilling & Completions

- Reservoir & Wells

- Operations & HSSE

Energy Value Chain

- Core Value Chain

- Overheads & Functions

- Capex & Opex

- Commercial, Engineering and Technical Metrics

- Budgeting and Targets

Profiles Tracked

- IOCs

- NOCs

- Independents

- Service Companies

- Finance

- Private Equity

Sample Domains

- LNG

- Conventionals, Unconventionals

- Offshore and Onshore

- Tight Oil (LTO), US Shale

- Thermal Oil Sands

- Long Cycle / Short Cycle

- Energy Intensity

- Pipelines and Terminals

Regions

- North America

- South America

- Europe

- Middle East

- Africa

- Asia Pacific

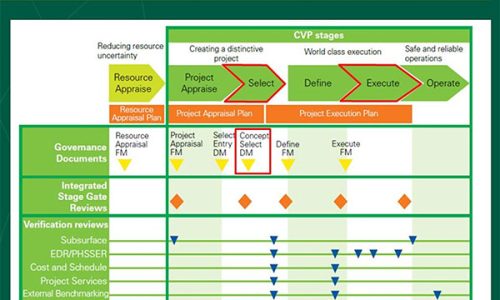

Our Methodology

Backed with over 24 years’ experience, we know how to provide accurate data.

Baselining

Read more >Benchmarking

Read more >Value Analytics

Read more >Terms of Reference

Read more >Validation & Assurance

Read more >Follow Through

Read more >Fulcrium Benchmarking Methodology Videos

Testimonials

We will continue to use Fulcrium as a secret intelligence resource: they have never failed to deliver and we value the advantages they bring to our benchmarking initiatives.

Global Supermajor

We have no doubts that they use impeccable sources and data collection methods. They have passed every test in terms of reassuring us about the origins and viability of the data.

Global Supermajor

We regard Fulcrium as offering significant value-add in their market space. They have a deep understanding of Oil & Gas benchmarking activity compared with the generic benchmarking firms.

Global Supermajor

Oil & Gas Benchmarking Data for Competitive Advantage

A small sample of peer companies Fulcrium tracks ...

Our Unique Database

Over two decades, Fulcrium has built a matchless database of transformation benchmarking data and market intelligence from major companies across multiple sectors and in many geographies throughout Europe, the Americas, the Far East, Middle East, Asia Pacific and Africa.

Insights gained from this multi-sector and global coverage are at the heart of our genuinely transformative benchmarking and value-identification services, and are the envy of other benchmarking providers and consultancies.

The result? Our global data consistently deliver evidence-backed exceptional-value opportunity-identification, and clients refer to us as their “highly valuable secret intelligence resource”.

Request a free consultation today to discuss your requirements.

Oil & Gas Benchmarking Expertise

Our expertise in Oil & Gas benchmarking has been used by numerous global companies. We couple our benchmarking expertise with a deep understanding of:

- Strategic relationships between nations, supply chain, operators and JV partners

- The dynamic industry structure

- Upstream, midstream and downstream value chains

- Business drivers, local and global challenges

- Engineering, technology practices and standards

- Interface issues between Capex and Opex

- Greenfield vs. Brownfield

Operator and National Oil Companies Benchmarking

Old business models and strategies will no longer serve in this new landscape, creating an urgent need for recognition of the power shifts, and comprehensive managed change.

The IOCs, including the five supermajors (ExxonMobil, BP, Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron and Total) are responding by increasingly operating at the margins – focusing on challenging environments including deep waters, pre-salt, shale formations, oil sands and tundra.

The risks are not just concerned with health and safety, and environmental sensitivities: many of these reserves are located in regions that are politically and environmentally sensitive.

It remains to be seen what impact the Arab Spring will have long-term on the political and economic landscape of the Middle East and North African region – certainly, there may be increased restrictions on the IOCs from both national governments and the NOCs.

Our proprietary Oil & Gas benchmarking service, proven tools and frameworks mean that we can undertake complex benchmarking engagements without delay.

Upstream Oil & Gas Operating Expenditure Cost Benchmarking

With the global economic outlook continuing to look uncertain, it is imperative to focus on bottom-line improvements and to control spending – and yet exploration requires ever-greater investment and the additional costs of this have had a profound impact on profitability.

Average operating profit margins for the supermajors fell from 15% in 2006 to below 8% in the year from late 2019 to early 2020.

Royal Dutch Shell is one supermajor that has made a commitment to long-term investment with a diversified portfolio: liquefied natural gas (LNG) in Australia, conventional oil in the North Sea, Gulf of Mexico deep water, and tight gas in North America. ExxonMobil, too, holds about 50% of its reserves in heavy oil, deep-water, and unconventional oil.

Upstream Oil & Gas Capital Expenditure Cost Benchmarking

Yet there is no alternative to increased expenditure.

Oil & Gas Operator Competitive Benchmarking

It is likely that the NOCs will gradually enter into fewer production-sharing agreements with other companies, making it even more critical that the IOCs can carve out defensible niches.

With global energy demand in 2040 predicted to be some 30% higher than in 2016 (according to ExxonMobil), they need to determine their role and implement strategies that align shareholder expectations with corporate capabilities, performance and market conditions.

Just some of the Oil & Gas benchmarking questions they need to answer are:

- Whether or not to relinquish shared resource ownership and adopt a contractor-operator service model

- Energy security in a world reliant on and impacted by politically-motivated behaviour of hydrocarbon-rich resource holders

- How to unlock value from mature assets and to optimise the overall performance of their entire asset portfolio

- How to reduce energy intensity and improve energy efficiency at every stage of the oil & gas value chain

- How Permian shale and Canadian oil sands plays can compete in a sustained ultra low oil price environment and with stringent greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions regulatory limits

- How to respond to new policy frameworks and regulation in a post-Macondo Well-Deepwater Horizon world

- How to achieve a 360-degree view of operations to aid strategic and operational decision-making

- The degree to which they collaborate with the NOCs on production-sharing

- Which NOCs will become true strategic partners (resource-rich ones such as Saudi Aramco, QatarEnergy, ADNOC, PDO, Petrotrin, SEPOC, Sonatrach, Sonangol, KazMunaigas, Gazprom and Rosneft or resource-poor ones such as Petronas, Petrobras, ONGC, GAIL, Petro SA, and Equinor)

- Which geographies offer the most long-term potential, and how to build partnerships with host governments

- What relationships to foster with ambitious service companies such as Halliburton, Schlumberger, Baker Hughes and Transocean

- What governance to put in place for partnerships, and how to ensure accountability in joint operations

- Where and when to invest in Unconventionals (low-margin, high capital-intensive plays)

- How to expand their total field management services and leverage their world-class project management competences

- How to retain a technological lead in areas such as subsalt imaging, sand screens, non-seismic geophysical exploration, and solvent-assisted steam-assisted gravity drainage (SA-SAGD)

- Which merger, acquisition and divestment opportunities to exploit to create infrastructure synergies and economies of scale, increase operating efficiencies, and unlock value

- How to centralise operations underpinned by best practices (the successful ExxonMobil model) or, if decentralisation is preferred

- How to ensure corporate-wide accountability and delegation

- How to simplify the organisation and ensure that every division, business unit and function (from Engineering to Technology) serves the wider goals of the business

- How to improve operational efficiencies, while maintaining safe & reliable operations, and reduce costs while protecting revenues and margins and funding increasingly expensive exploration

- How to integrate strategy and risk management as the primary drivers to steer business planning, budgeting and asset portfolio management

Upstream Oil & Gas Corporate Benchmarking

No one knows which of the IOCs will emerge as relevant players.

The losers will be relegated to low-margin service contractors, while the winners will be super-contractors, or super-project managers, operating alongside the NOCs and major service companies to exploit the traditional and new hydrocarbon assets wherever they are found.

The IOCs still have scale on their side, but they need to become more agile and competitive.

To be successful, the IOCs must constantly review, evaluate and benchmark the performance of their strategies.

Only then can they hope to optimise performance of their asset portfolios over the short, medium and long-term.

Shifting Sands for the IOCs

Just forty years ago, the national oil companies (NOCs) controlled less than 10% of the global oil and gas reserves.

Now they control more than 90% – giving them the dominant hand in attracting capital, technology and human resources across the value chain from deep-water reserves to refineries. On the back of the NOC’s growth, the oilfield service companies are flourishing, expanding and integrating their services and investing in technologies to facilitate surface- and sub-surface-based operations.

Now that the supremacy of the integrated oil companies (IOCs) is behind us, they face almost constantly shifting sands. New dominant players, new competitors, new combinations of partners – all need evaluating and responding to. Increasing operating costs, more onerous regulations, restricted access to capital, exploration challenges, skills shortages, the opportunities and threats posed by Unconventionals (c.f. Fulcrium Canadian Oil Sands Benchmarking and US Permian, Eagle Ford, Bakken, Niobrara shale basins Light Tight Oil – LTO Benchmarking), and environmental risks – all require a cohesive strategy if they are not to stifle growth.

Canadian Oil Sands SAGD Benchmarking

Just forty years ago, the national oil companies (NOCs) controlled less than 10% of the global oil and gas reserves.

Unconventionals Benchmarking

U.S. production of light tight oil (LTO) has increased significantly since 2010, driven by technological improvements that have reduced drilling costs and improved drilling efficiency in major shale plays such as the Bakken, Eagle Ford, and the Permian Basin.

Production from light tight oil plays surpassed 50% of total U.S. oil production in 2015 when light tight oil production reached 4.9 million per day (b/d).

Tight oil production and overall U.S. oil production are expected to increase through around 2030 in the US Energy Information Administration Reference case.

US Shale Benchmarking

There is no better example of the impact of sudden transformation on an industry than light tight oil and shale gas in the USA.

No-one envisaged even five years ago that the country would be able to leverage horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing to exploit reserves that, by current estimates from the US Energy Information Administration, amount to 862,000bn cu ft. It is the Permian that has been the strongest of the US shale oil regions in terms of crude production.

From peak levels in the first half of 2015, output in the Eagle Ford shale of south Texas has declined 29 per cent, according to the EIA, while in the Bakken formation of North Dakota it is down 17 per cent.

By contrast in the Permian, production is at record highs, up 19 per cent in the past year alone. This boom has been matched by steep rises in the share prices of some of the companies that focus on the Permian.

Gas from shale now accounts for over 30% of US natural gas production (and will rise to c. 47% by 2035) and has depressed domestic gas prices so profoundly that LNG projects have been rendered uneconomic.

This has left supermajors such as ExxonMobil sitting on an estate of billion-dollar LNG terminals that will probably never recoup their investment. However, as the shale gas, especially from the Marcellus Shale, have tested up to 16% ethane content (making it a low-priced feedstock for ethylene synthesis) this has resulted in a boom in new ethylene plants.

Unsurprisingly, China is pushing ahead with shale gas to replace its reliance on coal. In November 2009, Barack Obama agreed to share US gas-shale technology with China, and to promote US investment in Chinese shale-gas development.

A White Paper on energy development released in October 2016 by China’s government calls for a ramping up of the industry and pumping 6.5 billion cubic meters of natural gas from underground shale formations by 2018.

The IOCs are already lining up. Royal Dutch Shell has shale gas agreements with three major Chinese oil companies, and ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, and Total are also working to form shale gas partnerships with Chinese oil and gas companies.

The political landscape is shaping whether other regions are able to exploit shale gas as aggressively as the North Americans and Chinese.

There are vast reserves in South America; Royal Dutch Shell is using hydraulic fracturing in the Karoo region of the South African Western and Northern Cape provinces; India and the US are collaborating on identifying and exploiting shale gas resources; but Europe presents a mixed picture and, according to a 2016 report from the European Commission (https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/enOil & Gas/publication/eur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports/unconventional-gas-and-oil-resources-future-energy-markets-modelling-analysis-economic), shale gas production will not make Europe self-sufficient in natural gas. Poland has Europe’s largest reserves and companies including ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Talisman Energy, BNK Petroleum, and Marathon Oil are actively drilling. Ukraine has Europe’s third largest shale gas reserves, and Royal Dutch Shell and Chevron will start commercial gas production in 2017.

Further down the line, it may be possible to leverage shale technologies to unlock oil – potentially producing another seismic shift in the industry.

Permian and Eagle Ford Benchmarking

Production in Texas, the largest oil-producing state, is driven by two major oil-producing regions, the Permian and the Eagle Ford.

As defined in EIA’s Drilling Productivity Report, the Permian region makes up a large geographic area with producing zones each more than 1,000 feet thick and with multiple stacked plays.

“People just don’t seem to realise how big the Permian is. It will eventually pass the Ghawar field in Saudi Arabia, and that is the biggest in the world” – Scott Sheffield, founder of Pioneer Natural Resources and acclaimed ‘King of the Permian’.

Because of its large geographic size, the Permian offers a lot of potential for testing and drilling, and the multiple stacked plays allow producers to continue to drill both vertical wells and hydraulically fractured horizontal wells.

“Shale oil”, or the more accurate term “Tight oil”, is often used to refer to rock formations that contain oil and that sometimes might actually be shale. The defining characteristic is that the rock is not sufficiently porose or permeable to allow oil to flow out if all you do is drill a hole into the formation.

However, by fracing, if you create fissures in the rock by injecting water (along with sand and some chemicals to facilitate the process) at high pressure along horizontal pipes through the formation, oil can seep back through the cracks and be extracted.

Refining Operations Benchmarking

Crude oil is a highly variable mixture of heavy and light hydrocarbons that need to be separated in a refinery to turn them into usable products.

Three major types of operation are performed to refine the oil into finished products: separation, conversion and treating.

- Step 1 – Separation: The first is atmospheric distillation at 350 to 400°C. The crude oil vapours rise inside the column, while the heaviest molecules remain at the bottom. The heavy residues are distilled again in another column.

- Step 2 – Conversion: After separation, the next step is conversion at a temperature of 500°C. Processes include catalytic cracking and hydrocracking, which “crack” the molecules that are still too heavy, producing gas, gasoline and diesel.

- Step 3 – Treating: Then molecules that are corrosive or cause air pollution, such as sulphur, are removed.

GOSP: Oil Production and Processing Benchmarking

Most oil-producing wells are free-flowing. Once the oil is extracted, it is piped to a gas-oil separation plant (GOSP) where water and the majority of dissolved gases are extracted.

The remaining oil is then sent to a stabilisation facility, for final gas separation and removal of hydrogen sulphide.

The extracted gas is sent to gas operations facilities for additional processing, while the water is injected back into the ground. This oil is now dry (no water), sweet (no hydrogen sulphide) and stabilised (no gas), and can be refined or exported.

The profitability of a gas processing plant is determined by the levels to which processes, operations and performance are optimised, taking into account the complexity and technology of the plant. A substantial benchmarking database and sound understanding of key benchmarking drivers for the various KPIs is therefore critical to optimising profitability and performance.

Terminals and Pipelines Benchmarking

No one knows which of the IOCs will emerge as relevant players.

The losers will be relegated to low-margin service contractors, while the winners will be super-contractors, or super-project managers, operating alongside the NOCs and major service companies to exploit the traditional and new hydrocarbon assets wherever they are found. The IOCs still have scale on their side, but they need to become more agile and competitive.

To be successful, the IOCs must constantly review, evaluate and benchmark the performance of their strategies. Only then can they hope to optimise performance of their asset portfolios over the short, medium and long-term.

Combined Heat & Power (CHP) Benchmarking

Gas Turbine-Powered Cogeneration also known as Combined Heat & Power (CHP), is the production of electricity and heat from a single fuel source.

Powered by a gas turbine, a cogeneration plant efficiently captures heat which would otherwise be lost during the production of electricity and converts it into useful thermal energy.

A cogeneration plant is both flexible and reliable and because of its efficient use of energy, industrial-scale cogeneration is more economical and environmentally attractive than conventional fossil fuel power plants.

'

'